Does physical activity change in immigrants within the European Economic Area? A case study of Italians move to Norway

Physical activity (PA) is one of the lifestyle factors that most influence whether people live a long and healthy life. Not only does an active lifestyle make people live longer,but it also contributes to better mental health and, in general, a higher quality of life. In particular, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that, to improve and/or maintain good psycho-physical health, adults and elderly adults should engage in aerobic PA of light- or moderate-intensity (e.g., walking, cycling, swimming) for at least 150 min per week, or in aerobic PA of vigorous-intensity (e.g., running) for at least 75 min per week, or an equivalent combination of light-/moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA. The WHO also recommends performing exercises aimed at increasing muscular strength, flexibility and balance. Moreover, it is recommended to avoid, for as much as possible, to spend prolonged time in inactivity or sedentary behaviors (e.g., sitting at work or watching TV). In spite of the consistent evidence on the health benefits of PA, as well as the clear and simple guidelines for PA behavior, insufficient PA remains one of the leading risk factors for poor health and mortality worldwide (1). From a health promotion perspective, a major challenge in promoting PA is that this behavior is subjected to social gradients, with more vulnerable sub-groups of the population less likely to engage in sufficient PA levels or respond to PA promotion initiatives. In particular, studies have consistently shown that gender, age, educational level, and ethnic background are major social determinants of PA behavior (2–4).

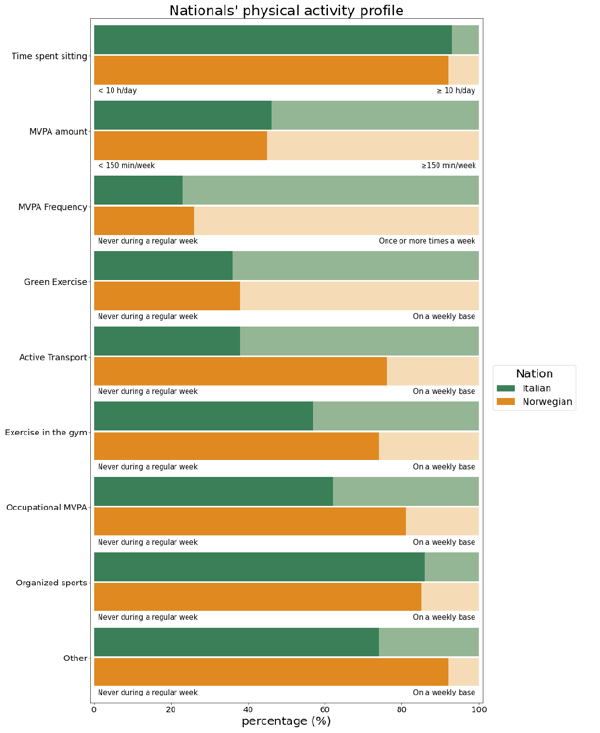

Figure 1. Physical activity profile of Italian immigrants in Norway compared with the Norwegian general population

Compared to other western countries, Norwegians are estimated to be relatively active. Figures from the Global Health Observatory indicate that, in 2016, 68% of adult Norwegians met the WHO’s recommended levels for PA (Figure 1). This prevalence was higher compared with other European countries such as, for example, Italy, where 59% of the adults engaged in sufficient PA levels. Moreover, compared with other countries, Norway shows a smaller gender-gap (Figure 1): while in Italy 54% of the men and 44% of women met the PA recommendations, in Norway 70% of men and 66% of women met the WHO’s PA recommendations. Italian immigrants in Norway, although still relatively low in number, are a rapidly growing group. Italians enjoy the right of free movement of people within the European Union and the European Economic Area (EEA; which includes Norway). Italians’ immigration to Norway has been steadily increasing since the establishment of the EEA Agreement in 1994, and it has 3-fold since the economic crisis of 2008 (5, 6). This trend is in line with the increased Italian mobility worldwide: from 2006 to 2019, the number of Italians registered as residents abroad increased by 70%, going from over 3.1 million to almost 5.3 million (5). These new waves of Italian immigrants have been often described as “the better youth” (young, well educated, cosmopolitan and mobile individuals), though there are also indications that grownups and families have been moving looking for jobs or better living conditions (6). According to figures from the Italian Embassy in Norway, to date 7.108 Italian citizens reside in Norway and are registered at the Norwegian Register of Italians Living Abroad (AIRE). Of these, 4.523 (2.862 men and 1.661 women) are Italian-born, while the others are progenies of Italian immigrants (6). In spite of this rapid increment, the living conditions of this group, especially in relation to their health and health-related behaviors such as PA, have received virtually no attention.

In a study of Calogiuri et al. (7) it was highlighted that a large majority of Italian immigrants in Norway perceived they were as or even more physically active in Norway than they would have been if they continued living in Italy. However, the prevalence of perceiving a negative impact was greater in specific subgroups (the men, older individuals, those who live in less urbanized regions of Norway, and those with lower socio-economic status). No significant differences between the Italian immigrants and the general Norwegian population were found for key indicators of PA levels, though some differences were observed in relation to specific activities. Associations of PA with different sociodemographic characteristics were observed, especially in relation to gender, educational level and, to a certain extent, age. In contrast with patterns observed in the general Italian population (as well as patterns observed in other immigration groups), women were generally found to be more physically active than men. These findings shed light on the PA habits of Italian immigrants living in Norway, a relatively small but rapidly growing immigration group and can be used to inform initiatives to promote PA in this or similar immigrations groups. This study indicates the potential of expanding the research on health and PA to under-researched immigrant groups, in particular within the EEA context. As mobility within the EEA is on the rise, it is important to understand how individuals interact with the opportunities and the culture of the country of resettlement, as well as how social gradients influence PA patterns in the context of migration.

Exploratories: Migration Studies, Sport Data Science

Sustainable Goals: Good Health and well-being

Reference:

1. World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity Sedentary Behaviour. Geneva:World Health Organization (2020).

2. Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson KA, Kraft MK, Kerr J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu Rev Public Health. (2006) 27:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100

3. Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brown W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2002) 34:1996–2001. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020

4. Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. (2012) 380:258–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1

5. Fondazione Migrantes. Rapporto Italiani nel Mondo 2019 [Report Italians in the world 2019]. TaAV editrice. (2019).

6. Miscali M, Calogiuri G, Terragni L. ≪Bene, ma non benissimo≫: le nuove mobilità degli italiani in Norvegia [“Well, but not very well”: new mobilities of Italian immigrants in Norway]. (2020).

7. Calogiuri G, Rossi A and Terragni L. Physical Activity Levels and Perceived Changes in the Context of Intra-EEA Migration: A Study on Italian Immigrants in Norway. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:689156. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.689156