"Girls Just Wanna Have Fun?” Participation Trends and Motivational profile in women during sky events

Exploratory: Sports Data Science

Mass participation sporting events (MPSEs) have been defined as sporting competitions “where the primary focus is on promoting participation and engagement rather than the significance of the sporting outcome” (Coleman and Ramchandani, 2010). In contrast with other popular sporting events that receive large coverage in the media, such as the Olympic Games and different world championships, a characteristic of MPSE is that they not only attract elite athletes but, in the spirit of “sport for all” ideals, they primarily target recreational sport practitioners. This, alongside the fact that MPSEs have experienced a large increase in popularity across the world in the last three decades, means that MPSEs have been increasingly viewed as a possible vehicle for health promotion (Murphy and Bauman, 2007; Murphy et al., 2015). In particular, MPSEs can provide a motivational goal for people who intend to start exercising regularly or for those who want to enhance their exercise routines.

Globally, women have lower physical activity levels than their male counterparts (World Health Organization [WHO], 2010, 2018; Hallal et al., 2012). Over the past few decades, however, women’s physical activity levels in many high-income countries have increased. In the United Kingdom, for example, the prevalence of women meeting the minimum recommendations for physical activity is almost equal to men’s and in Norway, the prevalence of sufficiently active women is slightly higher than that of men. While women’s high levels of physical activity are generally mainly driven by activities such as walking and exercising in fitness centers, their participation in other sporting activities such as running and biking tends to be lower compared to men. In line with this pattern, in Norway, women’s participation in cross country skiing is relatively high, though lower than that of their male counterparts.

To boost women’s participation specifically, many MPSEs offer women-only races, which typically take place on shorter and/or less challenging routes and are characterized by a less competitive atmosphere. Some studies suggest that women-only races not only catalyze women’s participation in MPSEs, they also may help them maintain high physical activity levels over the years (Crofts et al., 2012; McArthur et al., 2014). While the addition of women-only races might be effective in boosting women’s participation in absolute terms, enhancing the inclusiveness of women in main MPSEs may also have advantages, such as contributing to reducing gender stereotypes in sport as well as stimulating even greater amounts of exercise among female participants. Moreover, these events are likely to attract women who have different characteristics, motives, and aspirations than those who would rather enter the main MPSE. In particular, it is plausible to assume that women in the main MPSEs have higher levels of physical training and are more interested in their performance, as opposed to the participants in women-only races, who may attach more importance to the social context and supportive and celebratory atmosphere of the event.

In the present study, we focus on a particular MPSE, the Birkebeiner races (BRs). The BRs are an iconic Norwegian cross country ski (classic technique) MPSE, which takes place in the region of Oppland (Inland Norway) and registers over 10,000 participants every year. The challenging 54 km trail goes through open and forest terrains, crossing two mountains (820 and 760 m above sea level). In 2018, the main BR celebrated its 80th edition; the race was launched for the first time in 1932, and since then it has been organized annually, except in the war years 1941–1945 and few other times because of adverse meteorological conditions. Alongside the main race, the event includes different variants: the Friday, the half-distance, and the women-only races. The Friday race takes place on the exact same trail two days before the main BR, and is generally characterized by fewer participants attending. Differently, the half- (28 km) and the women-only (15and 30 km) races are characterized by shorter and less challenging (relatively to the main BR) tracks. For instance, the track of the women-only 15 km race has only one major up-hill (about 550 m above sea level).

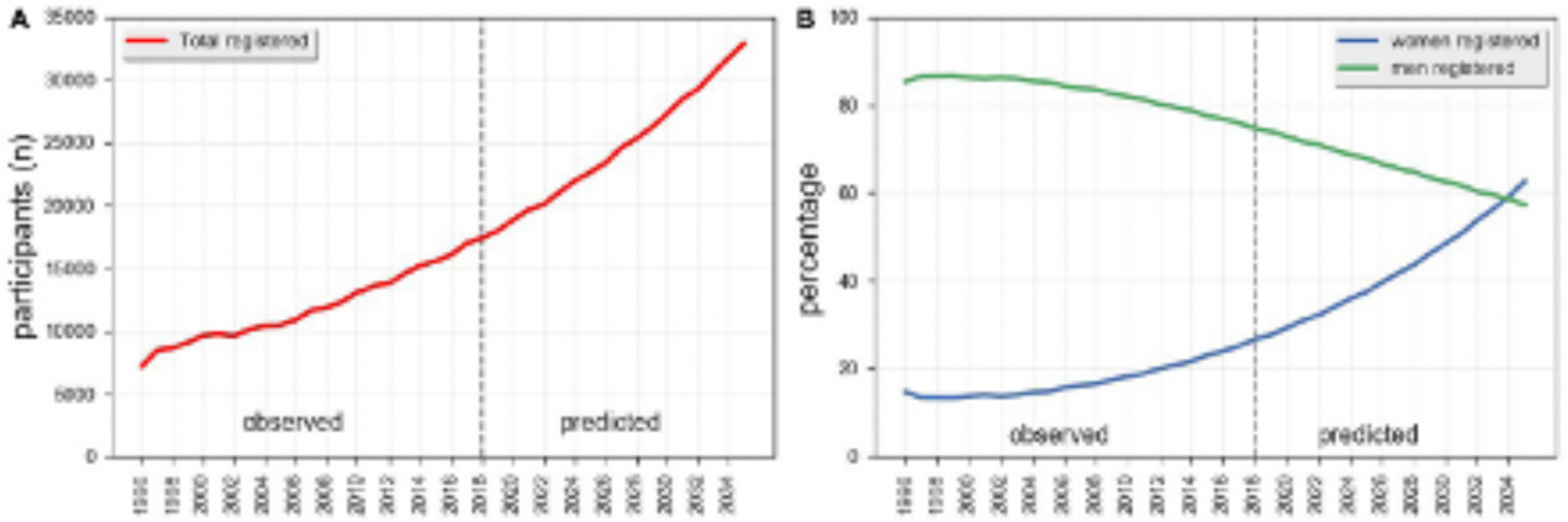

In the 17-year span between 1996 and 2013, the number of women participating in the main BR has trebled, though it dropped in the period 2015–2018. A predictive model confirms this trend (Figure 1), predicting a decrease in the percentage of male participants entries in favor of a relative increase in the women’s. The relative prevalence of women in the main BR since 2010 was generally low of about < 20%. However, it is possible to predict a future increment of women in the main BR with women’s ratings possibly matching the men’s by the year 2034. According to the outcomes of our model, if this trend persists, it would take about 15 years for the prevalence of women in the main BR to match the men. Moreover, the model predicts an increase in the total number of participants in the main BR for future years, indicating that the number of women in the main BR is likely to increase both in relative and in absolute terms. The introduction of the BR variants (Friday, the half-distance, and the women-only races) seems to have contributed to boosting women’s participation in the MPSE both in absolute and relative terms. In 2018, for example, the presence of the women-only races brought almost 1,600 women into the event, resulting in an increased overall prevalence of women from 20% to 30%. The presence of the women-only races also contributed to buffer the drop in women’s entries during the period 2015–2018.

Figure 1. (A) total participants and (B) percentage of men and women registering in the main race.

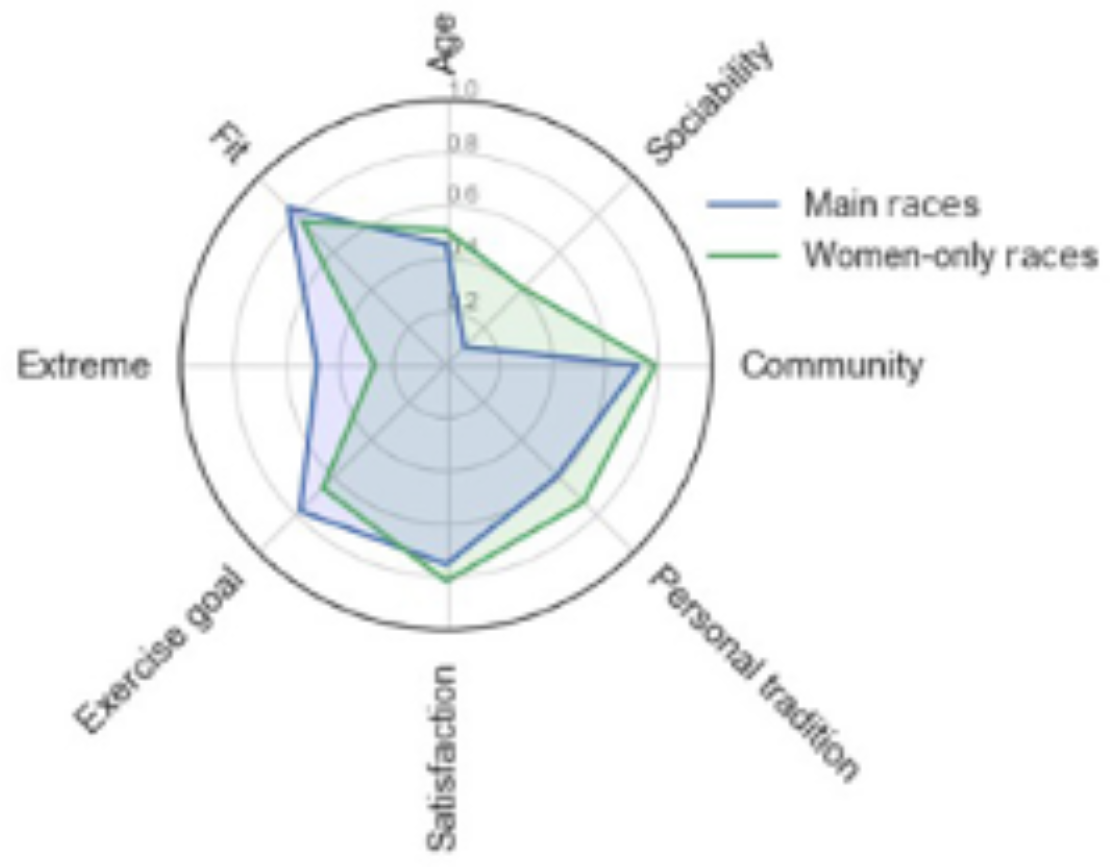

Figure 2 shows that participation in the women-only races was predominantly driven by the sociability motives and seeing the race as a tradition, the women in the full-distance races were predominantly driven by a performance-oriented motivation, and showed a desire to compete and feel “fit” and “pushing boundaries.” Both groups of women perceived the race as enjoyable, although those in the women-only race tended to report higher ratings of satisfaction than the women in the full-distance races. Our findings are partly in line with previous research showing that sport participation, compared with other forms of exercise (e.g., exercising in the gym), is primarily driven by more autonomous forms of motivation, such as mastery, enjoyment, and sociability (Frederick and Ryan, 1993; Kilpatrick et al., 2005; Calogiuri and Elliott, 2017). These same motives were indeed found to be important for women to enter the main BR or one of its variants. At the same time, our study emphasizes how participation motives are also largely related to the specific context of sporting events, as, for example, that of the full distance races (for which participation was predominantly characterized by mastery- and performance-oriented motives) compared to that of the women-only races (for which participation was predominantly characterized by sociability oriented motives). In summary, across all races, most of the women were physically active, of medium-high income, and living in the most urbanized region of Norway. Satisfaction and future participation intention were relatively high, especially among the participants in the women-only races. “Exercise goal” was the predominant participation motive. The participants in women-only races assigned greater importance to social aspects, and perceived the race as a tradition, whereas those in the full distance races were younger and gave more importance to performance aspects.

Figure 2. Radar chart of the features with highest explained variance (normalized Gini coefficient) in a logistic regression model predicting women’s participation in either the full-distance races (main race or Friday variant) or one of the two women-only races (15- or 30-km variants). Values expressed as the means of the questionnaire answers normalized to 0–1 range. Note: Sociability = “My friends did it” (participation motive); Community = “Part of a community” (self-perception); Personal tradition = “I usually participate every year” (participation motive); Satisfaction = Overall satisfaction with the race; Exercise goal: “A good exercise goal for the season” (race-perception); Extreme = “Extreme” (self-perception); Fit = “Fit” (self-perception).

In conclusion, the results from this study shed light on women’s participation in an iconic MPSE in Norway. Considering that in Norway levels of sport participation among women are relatively high, and that cross-country skiing is (still) embedded in the national identity of the population, this context offers interesting insight into the larger topic of women’s participation in MPSEs. In general, the findings corroborate known patterns in MPSEs, especially with respect to: (i) low involvement of women, as well as other disadvantaged sub-groups (e.g., women with lower socioeconomic status and low physical activity levels); (ii) indication of a progressively increasing prevalence of women in the main race; (iii) different sociodemographic and motivational profile of women engaged in different races (especially when comparing full-distance vs. women-only races). On the other hand, novel and encouraging findings have also been highlighted, such as a relatively large involvement of local communities, indicating some potential benefits in terms of exercise promotion in a region with higher prevalence of insufficiently active individuals (rather than, for example, to MPSEs taking places in major cities). Moreover, by focusing on women’s participation across different races, our findings show that the specific race context plays an important role in broadening and supporting women’s inclusion in sporting events. It is worthy of note, however, that the combination of the main race and its variants seems to be a good strategy for locking people in to participation over time as they age and develop different interests.

Written by: Alessio Rossi

Revised by: Luca Pappalardo

REFERENCES

Coleman, R., and Ramchandani, G. (2010). The hidden benefits of non-elite mass participation sports events: an economic perspective. Int. J. Sports Mark. Sponsorship 12, 19–31. doi: 10.1108/ijsms-12-01-2010-b004

Murphy, N., and Bauman, A. (2007). Mass sporting and physical activity events—are they “bread and circuses” or public health interventions to increase population levels of physical activity? J. Phys. Act. Health 4, 193–202. doi: 10.1123/jpah.4.2.193

Murphy, N., Lane, A., and Bauman, A. (2015). Leveraging mass participation events for sustainable health legacy. Leis. Stud. 34, 758–766. doi: 10.1080/02614367.2015.1037787

World Health Organization [WHO], (2010). Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization [WHO], (2018). Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Hallal, P. C., Andersen, L. B., Bull, F. C., Guthold, R., Haskell, W., Ekelund, U., et al. (2012). Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 380, 247–257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1

Crofts, C., Schofield, G., and Dickson, G. (2012). Women-only mass participation sporting events: does participation facilitate changes in physical activity? Ann. Leis. Res. 15, 148–159. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2012.685297

McArthur, D., Dumas, A., Woodend, K., Beach, S., and Stacey, D. (2014). Factors influencing adherence to regular exercise in middle-aged women: a qualitative study to inform clinical practice. BMC Womens Health 14:49. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-49

Frederick, C. M., and Ryan, R. M. (1993). Differences in motivation for sport and exercise and their relations with participation and mental health. J. Sport Behav. 16, 124–146. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3407-0

Kilpatrick, M., Hebert, E., and Bartholomew, J. (2005). College students’ motivation for physical activity: differentiating men’s and women’s motives for sport participation and exercise. J. Am Coll. Health 54, 87–94. doi: 10.3200/jach.54.2.87-94

Calogiuri, G., and Elliott, L. (2017). Why do people exercise in natural environments? Norwegian adults’ motives for nature-, gym-, and sports-based exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:E377.