From Tweet to Theft: Tracing the Stolen Cryptocurrency from the UNI scam on Twitter

Cryptocurrencies have the potential to revolutionize the world of finance, providing individuals with more freedom and trustless services. However, this new paradigm also comes with high risks for inexperienced users. With the growing popularity of cryptocurrencies, fraudsters are increasingly leveraging social media platforms to spread malicious messages, aiming at deceiving users and gaining control over their funds. A prevalent type of scam is the fake giveaway, where scammers persuade victims into sending their crypto tokens with the fake promise of receiving more in return.

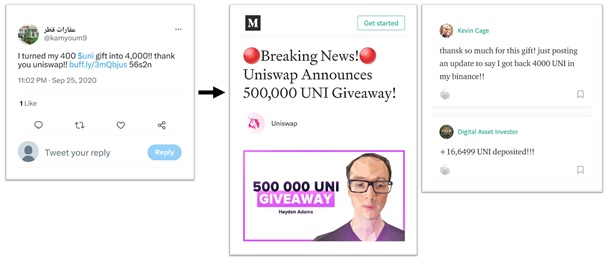

Figure 1: Tweet from a fake account and fake giveaway blog post.

In a previous study on coordinated and inauthentic behavior on Twitter ("Ready-to-(ab)use: From fake account trafficking to coordinated inauthentic behavior on Twitter"), we exposed a fake giveaway related to the Uniswap token UNI. In September 2020, 146 accounts for sale on the Russian website buyaccs.com were exploited to post over 140,000 tweets. The scheme adopted is shown in Figure 1. A tweet claims to have turned 400 UNI into 4,000 and shares a link. The link directs users to a blog post detailing the fraudulent giveaway of Uniswap (UNI) tokens. The post includes fake feedback from grateful users, as well as an address on the Ethereum blockchain where the UNI should be sent to take part in the giveaway. Notably, Twitter systems were mostly ineffective in countering this operation, as 97 accounts out of 143 were still active at the end of 2020.

Ethereum is an open-source, public, and decentralized blockchain designed for building decentralized applications (DApps). Uniswap is a popular example of DApp, a decentralized exchange where users can "swap" tokens without the need for a third party. UNI is the governance token of Uniswap, and it was "airdropped" to Uniswap users in September 2020, a few days before this scam operation started. Indeed, the scammers cunningly exploited the hype surrounding the launch of the new token.

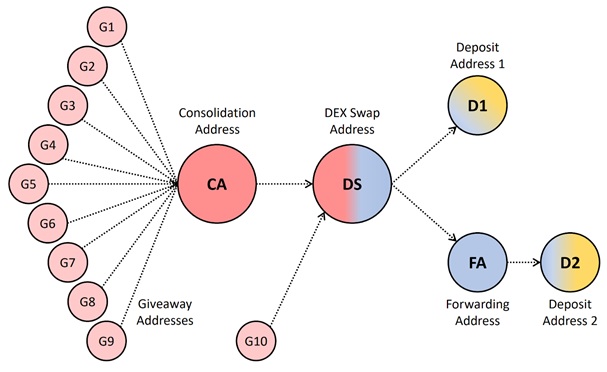

Figure 2: Graph describing the addresses and transactions used by the scammer.

Thanks to the public and immutable nature of the Ethereum blockchain, we were able to reconstruct the scammer's activity starting from a single piece of information, namely one of the addresses used to collect funds from victims. The result of this analysis is shown in the diagram in Figure 2. The scammer used at least 10 "giveaway addresses", i.e., addresses that were advertised to victims using the fake blog post. In a short period between September 18 and 28, 2020, these addresses received a total of 20,809 UNI tokens, worth over $100,000 at the time. On September 28, most of the UNI tokens were sent to a "Consolidation Address". About one month later, all the UNI tokens were amassed to another address which we named "DEX Swap Address" (DS). Indeed, at this point, the scammer converted the UNI into ETH (the native cryptocurrency of the Ethereum blockchain) using a decentralized exchange platform (DEX). Finally, the resulting ETH was split into two parts and sent to two deposit addresses, D1 and D2. More precisely, part of the ETH was sent directly to D1, whereas the remaining ETH was sent to a forwarding address, which immediately "routed" the ETH toward the second deposit address D2.

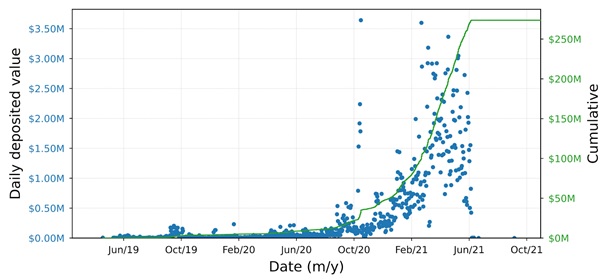

Figure 3: Daily and cumulative deposits made to deposit address D2.

Dedicated deposit addresses are generated by centralized exchanges (CEXes) for customers so that they can deposit their crypto to the centralized platform. On a CEX, like Coinbase or Crypto.com, users can then trade their crypto for other crypto or fiat currencies using the interface provided by the CEX. Moreover, they can withdraw the crypto to a different address on the blockchain, or fiat currencies to a bank account. After receiving funds from customers, CEXes typically move the crypto to a limited set of addresses, where the funds from multiple users are combined for more effective management.

Hence, after a deposit, the traceability of individual funds on the blockchain is lost, as only the CEX keeps an internal track of customers' balances. Nevertheless, we were still able to retrieve interesting information from these deposit addresses. First of all, the two addresses are controlled by Binance, meaning that the scammer(s) used the popular CEX Binance to deposit their funds. Second, we could evaluate the volumes of deposits made by the scammer over time. The findings from this second analysis are staggering: the scammer deposited crypto worth over $3 million into D1 and an astonishing $270 million into D2. The plot in Figure 3 shows a view of the deposits made to D2. Each blue dot represents a total daily deposit, with the USD equivalent value shown on the left axis and the cumulative deposited value on the right axis. This deposit address was mostly active between May 2019 and June 2021, with average daily deposits worth around $360,000. Notably, there were 32 daily deposits worth over $2 million, and three single transactions worth over $1 million.

This case study shows how blockchain analysis can facilitate the linkage of malicious transactions. In this case, the UNI scam proved to be just the tip of the iceberg, revealing a much larger activity. Despite the significant amounts involved, the scammer managed to keep using their Binance accounts for a relatively long time. It is thus reasonable to suppose that the scammer was able to withdraw the funds to different blockchain addresses or even to a bank account.

The findings of this study yield two important insights. First of all, the UNI scam orchestrated by coordinated and inauthentic accounts emphasizes the need for better control over fake accounts and malicious content on social media. Regarding the cryptocurrency realm, these results urgently call for more stringent measures to detect suspicious activity to protect the users of CEXes. As future research directions, we aim to expand the graph of transactions from this and other scams to possibly reveal common and detectable patterns. A better understanding of scammers' tactics could be beneficial to design automated techniques to help CEXes detect suspicious deposit addresses and mitigate the plague of illicit traffics on the blockchain.

Reference paper and public dataset:

This study has been presented at the Italian Conference on Cybersecurity (ITASEC 23):

Cola G., Mazza M., & Tesconi M. (2023), From Tweet to Theft: Tracing the Flow of Stolen Cryptocurrency, Proceedings of the Italian Conference on Cybersecurity (ITASEC23), Bari, Italy.

A preprint of the paper, as well as the dataset used for this study, are available in the Catalogue of SoBigData:

https://data.d4science.org/ctlg/ResourceCatalogue/uni_fake_giveaway_dataset